|

and improved neighbor relations, in addition to the obvious bonus of pasture

fertilization. "I see manure composting as a win-win," Blickle says. "Another

bonus-the

heat in the process destroys pathogens and breaks the parasite cycle."

Composted manure is a valuable soil amendment. "It makes plants

heartier and more disease-resistant. It's odor-free, so there are no complaints

from your neighbors. And no flies," Blickle points out. There are

fewer concerns about nutrients leaching, since composted manure retains

its nutrients.

The best way to turn a problem into an asset is to put manure in a pile

four feet in diameter and at least four feet high, and think of it as

a living organism that needs air and water. "Too much or too little

of either will upset the composting process," Blickle advises. "Yes,

you can turn it with a pitchfork regularly, but using a passive approach

is best."

Once you make your four-foot pile-and keep it at least 200 feet from

the barn-you need to aerate it. Blickle recommends putting a couple of

PVC pipes through the middle to make sure air circulates. Or take a tamping

rod and wiggle a hole in the pile. "You want air, you want it to

stay aerobic. It should smell organic, like soil. If there are bad odors,

then something is not right," she says.

The compost pile should stay about as damp as a rung-out sponge, Blickle

says. Too wet and it will rot; too dry and the process stops.

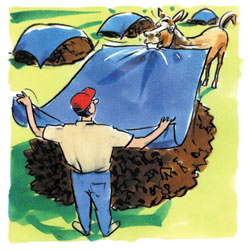

Cover the pile with a tarp. Any tarp will do, whether an old vinyl shower

curtain or a snazzy UV-resistant, composting-only sheet. "You need

to control moisture, and the tarp is the best way to do it, especially

in a rainy season. This is how you keep those sediments and nutrients

in the compost instead of in someone else's yard. Environmentally speaking,

if you do nothing else, cover your manure pile."

When rain is not a problem, keep the pile wet. Hose out your mucking-out

wheelbarrow with water till it's soupy and dump it on the pile. Keep the

compost damp, but not soggy.

Stall bedding adds another quotient to composting. "The natural

balance in manure between carbon and nitrogen is about 30 to 1. That's

perfect for composting," explains Blickle. "But in a lot of

commercial boarding situations, there's so much bedding in the stalls,

that the ratio goes up to 200 to 1. The problem is compounded if the stall

is bedded with evergreen shavings, which take a very long time to compost.

The best compost has as little bedding as possible; make use of rubber

floor mats instead," she advises.

Although mushroom growers and other agricultural enterprises might love

straw stall waste, it's not great for backyard composting. "Recycled

newspaper bedding is an excellent product, and many academic studies show

it's dust-free and very absorbent. It composts faster and hotter,"

Blickle notes.

She advises looking around your area to see what others are using. Don't

forget to visit with your veterinarian about your bedding choice, especially

a new choice, to make sure it's not toxic to your horse.

Blickle applies compost when plants are growing and can best utilize

the nutrients. She limits the application to four inches per year, and

not more than one-half inch at a time.

"That might sound like a lot, but it's not," she says. "It

usually ends up that you need more compost. I have five horses on four

acres, and I don't have nearly enough compost."

If you don't want to use the compost, friends and neighbors may welcome

it for their gardens and lawns. "I've even known people to be creative,

bag their compost, and sell it at a little roadside stand," Blickle

says.

Contact your local Conservation District, the USDA Natural Resource Conservation

Service, or local Extension office for more information.

|